The book is, in some ways, a botanical enterprise: pages from hemp, linen, cotton, and later pulp, boards from wood, iron gall ink. Perhaps it is natural, then, that the ideas that fill its pages would so often, and for so long, return to the vegetable world: in scientific and medical discourse, in theology, in verse, and in fiction. The books gathered in this collection represent each of these perspectives present in European and American written tradition.

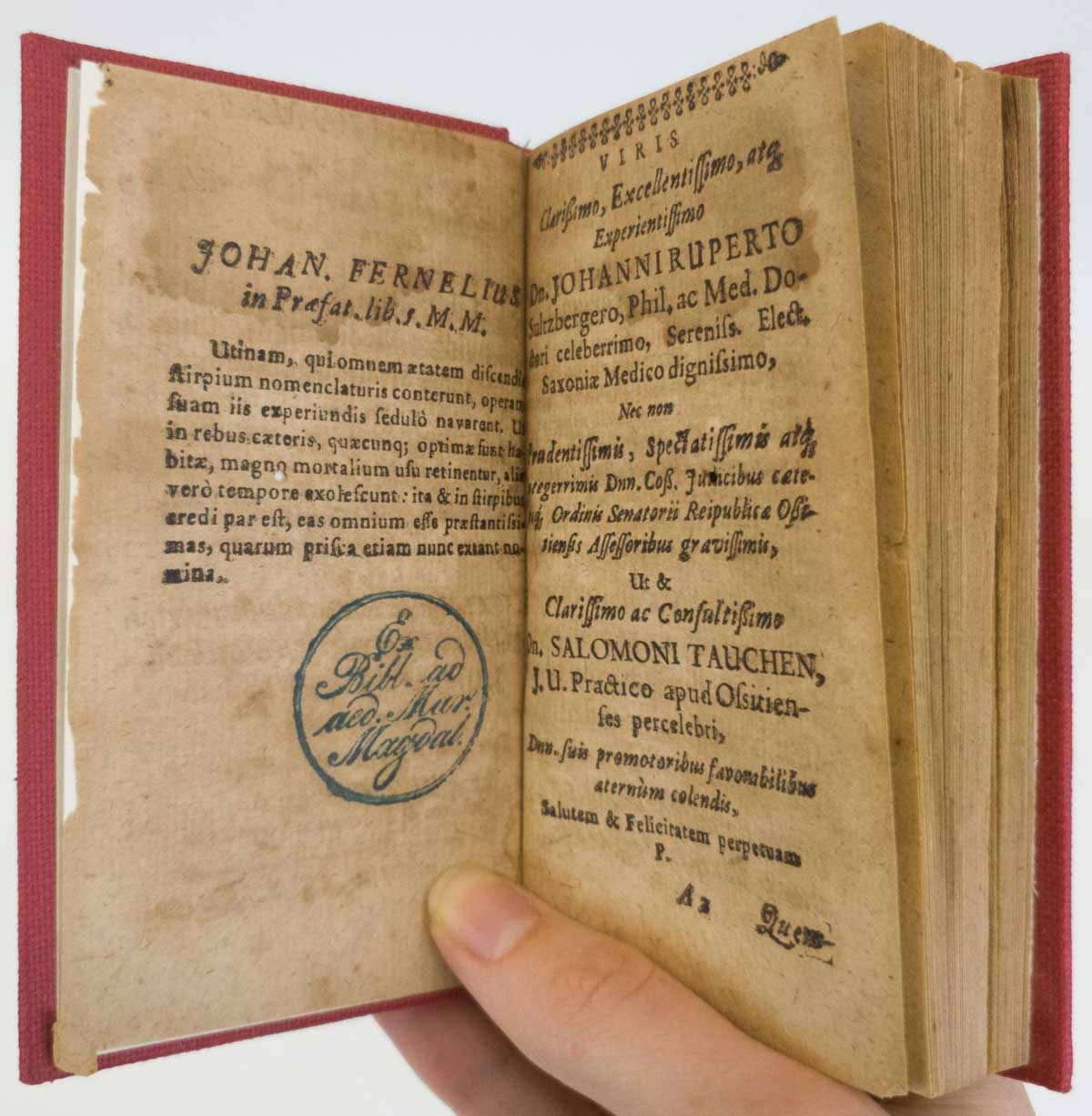

Among the scientific and medical approaches to written botanical scholarship, the tradition of writing materia medica, an outgrowth of classical tradition, and herbals, a continuation of medieval medical practice, is particularly robust. Works of this kind (such as Lonitzer’s Vollstandiges Krauterbuch and Blochwich’s Anatomia Sambuci) were primarily utilitarian in nature, concerned with the nutritional, medicinal, or toxic attributes of particular plants, and reflecting the priority placed on practical botanical knowledge by centuries of European plant experts.

Beginning in the 16th century, the combined impact of an array of scientific developments, including the arrival of novel botanical specimens on European exploration vessels and the development of the earliest microscopes, began to shift botanists’ focus from a utilitarian perspective to a more encyclopedic approach. Although herbals and materia medica continued to be published, a new generation of botanists (such as the English botanist John Parkinson) began to extend their efforts beyond plants deemed “useful” to the entire spectrum of botanical life.

As printing processes became increasingly sophisticated in the 19th century, yet another form of encyclopedic botany developed: scientifically-minded works with beautifully printed plates, intended as much to display the artists’ and printers’ skill as to provide botanical insights. A magnum opus of this category is Henry Frederich Conrad Sander’s Reichenbachia, whose chromolithographs required as many as twenty inks per image followed by hand-finishing with pigments and gum arabic.

It might seem that the publication of weighty academic tomes such as the Reichenbachia, which was the fruit of years of labor and massive expense, has little to do with the plants depicted in poetry and novels. Yet the scientific study of botany did inform its literary interpretations and in no case more clearly than Erasmus Darwin’s The Botanic Garden. Darwin saw great poetic potential in the taxonomic system developed by Carl Linnaeus and set about grafting poetry to Linnaean ideas. Though little read or studied now, the result of this effort, The Botanic Garden, was a great commercial success and a much-discussed work in its day. Darwin is credited both as an influence on the English Romantics and as the author of the first work of popular science.

Still, most examples of literary botany take a less overtly scientific tack. In such cases, authors incorporate plants into their narratives, not merely as components of a setting or to establish a particular atmosphere, but as central metaphors, contributors to plot, and even, on occasion, as characters. Milton’s Paradise Lost is low-hanging fruit as an illustration of plants as a central element of plot. Plants also feature as key metaphorical devices in Milton’s writing (for instance, in “Lycidas,” included in Milton’s Complete Works) as they do in the writings of later poets, from Shelley to Frost. Among novelists, plants occasionally feature as characters with significant influence on the unfolding of the plot, as in the case of Tolkein’s Ents and Rowling’s Whomping Willow. Plants on the Page draws these fantastical inventions into conversation with the historical effort to better understand the world of plants.